As a young undergraduate, I remember researching my first term papers and take-home exams, flexing my new-found research skills to find the absolute best references. At first, I equated “best” with “newest.” This wasn’t necessarily a product of my training; my undergraduate advisor teaches ecology from Foundations of Ecology, which starts with Forbes’ 1887 paper on The Lake as Microcosm and ends in 1970 (Foundations of Biogeography

goes even further, beginning with Linneus in 1781). Our society is obsessed with novelty in general– we want new models, new editions, new releases, so why not new science? I am happy to say that, perhaps because of my advisor’s emphasis on history, I quickly outgrew the tendency towards novelty, and learned to value the importance of Reading Old Things.

Historians have a word for Reading Old Things: historiography. Historians of science do it for a living. Why don’t scientists read (and cite) Old Things more often? I don’t mean just the classic 19th century examples, either– for some fields, anything older than 10 years is considered out-dated. A common answer I hear is that reading takes up precious time, and it can be difficult to keep up with the emerging ideas in new publications, let alone exploring the papers of the past. I think it goes beyond time management, though. I wonder if the ways in which we fund, do, write about, and report on science have influenced how much we value the research of the past?

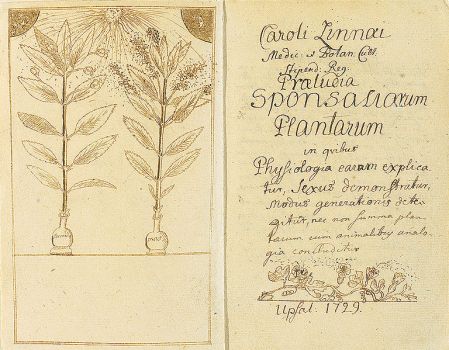

Pollination depicted in Linneus' Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum, 1729. They don't make 'em like they used to.

In the Geographical Distribution section of Darwin’s Origin, one finds hints of vicariance, land bridges, continental drift, species-area relationships, coevolution, sea level change, invasive species, and island biogeography, in many cases a century before such concepts became a part of the academic mainstream. Focusing on the recent leaves out an historical perspective on the intellectual development of one’s field, but it could also mean that some really cool ideas are left by the wayside. Conversely, some classic concepts that get distilled and replicated ad nauseum in biology textbooks (I’m thinking MacArthur’s warblers* here) could stand for a bit of primary scrutiny.

Reading Old Things has served me well; for my masters thesis, I took an observation from a paper in 1987 and used it to test an hypothesis about the influence of mammoths and other large herbivores on novel plant communities. When people ask me how I came up with such a clever idea (using spores from a dung fungus to reconstruct the timing of the extinction of ice-age herbivores), I tell them I didn’t: Owen Davis did. I just read about it in my perusals of paleoecological literature as an undergraduate. I wonder how many other gems are out there, buried in the back issues of medium-weight journals?

Here’s an idea for you professors out there: Assign your students to write two review papers or exam questions on the same subject. For the first, they are to use only research published before a particular year. For the second, they can only use papers published after that year. This should accomplish two things: First, students will have a better appreciation for how ideas change through time. Secondly, they should come away with a better understanding of the value of both old and new. This could be a fun exercise for science writers to try, too (blog ideas, anyone?).

The next time you do a search in Google Scholar and find yourself about to exclude the results to the most recent years, stop and think for a moment. Do you really need the most recent, or do you want the most useful? The two may not be the same. To close, I’ll leave you with one of my favorite Old Things to read, T. C. Chamberlain’s The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses, originally published in the late 19th century. This paper should be required reading for any young scientist-in-training (or science writers, for that matter).

*As an undergraduate, the aforementioned advisor took us to see MacArthur’s spruce trees. Not only did I not see a single spruce tree that resembled anything like the textbook diagrams, but I have serious doubts as to the ability of anyone to tell anything about niche partitioning among warblers in those trees.

Categories: Academia Commentary Education Grad School

Nice post, I’ve been reading Foundations of Biogeography lately. In some of those early papers it’s pretty cool seeing how they put together their hypotheses based on the extent of their knowledge at the time. Because their theoretical knowledge is so different from what we know now (no plate tectonics, no knowledge of glacial cycles) you can really see the theoretical frameworks they use to generate hypotheses.

We’re so surrounded by our own knowledge that sometimes we don’t realize how elegant our own hypotheses are and just assume they’re common knowledge. I think I need to go get a coffee. . .

LikeLike

I love reading older papers. Although, I may be skewed in my definition of old. Paleoclimatology is a fast moving, methods-based field and a relatively young one too. Even papers published post-1990 can sometimes be very outdated because of new, refined proxies and better quantitative estimates (eg. speleothem based reconstructions really took off in the late 90s). However, landmark papers (Urey [1947], Emiliani [1953] etc) are still cited quite frequently today. I wonder if this the same for other fields, say, ecology? (though I’m sure the classics are much older)

That said, my (only) paper cites Pearson [1901] & York [1966] !

LikeLike

Back in the days, everything was better! Yes I know that’s not true, but back in the days it was often the rich who could just pursue their scientific interests without having to worry whether some funding agency would find their ideas hip and happening. And without having to teach or do endless admin. And it’s good science is now open to those without massive inheritances to cater for our needs, but the advantage of the old system was that if you were one of these proviliged rich kids, you had all the time in the world! I mainly work in micropalaeontology, and the work resulting from, for instance, the Challenger cruise is still invaluable. Who can afford nowadays to send a ship off for several years, and then publish such extensive and detailed reports? Nobody. I’m glad that work is still out there for us…

And I love that idea of writing two essays with two separate subsets of literature!

LikeLike

I think also it can be perceived as kind of pompous to cite old stuff. In lab group we read a paper that cited Darwin (unnecessarily, I think) and there were more than a few rolling of eyeballs.

LikeLike

I think there’s a few factors going on here, all of which relates to the way science is conducted these days.

Firstly, depending on how people use database searches, the top results which come up are usually the newest ones, and it’s simply easier to browse through the first few pages and pick out a few key papers which support you claims or whatever. Also, results on ISI Web tend to be a bit sketchy on stuff which are pre-1970 – though in that case, you can turn to Google Scholar or other databases.

Secondly, these days with grant writing (and to some extend manuscript-writing), you often have to show that you research is fresh and new and “high impact” so you need to cite very recent papers (from the last year or two) to show how your work is on the “bleeding edge” of science to show that “Look, this is a very ‘hot’ topic at the moment that is moving places rrrreeeaally quickly – fund/publish/cite me!”. The concern is that if you cite anything considered a bit “old” then whoever it is on the receving end of your grant proposal/manuscript will go “Pfff, that dusty old crap – whatever!”

There’s a tendency to think that “old” is not as good as “new”, old stuff are not treated with much respect – even though some papers are considered as “classics” and some papers report on things which have been sitting in obscurity simply because their topic had fallen out of fashion (and not necessarily because they are any less important), but nevertheless contains extremely valuable information and insight. I can recall a number of times where I’ll be reading a paper and think “Hang on, there was a paper from 1973 that said this exact thing! What do you mean it’s *new*?” You can attribute this to laziness on the part of some people with their literature search, and not having a historical context to their own field, but even more disingenuinely, some people might even do this to make it out as if they are the first to have that particular insight.

In addition to that, I have also found some very valuable (and sometimes decades-old) papers which are not published in English but document some very good quality work – the type of research which are not glamourous at all (so forget about getting it funded in the current environment!) but are admirably meticulous and thorough in their execution.

I’ll keep your idea in mind about assigning students to write review papers based on research published before a particular year – it will give the student a good historical context on the topic and realise that science is an ongoing process. Of course, if I go ahead with it, I’ll make sure to credit you with the idea!

LikeLike

I think you’re spot-on, and eloquently detailed what I hinted at in my post. I, too, have found ideas and results in older papers that I’ve seen recycled in? Ignored by? new papers, and wondered if people just don’t realize what they’re missing or if it’s deliberate. For some things, like field ecology, methods haven’t changed so terribly much as to warrant ignoring the older papers.

LikeLike

Yes, I absolutely agree with your point on research as such field ecology. I can understand that with certain fields such as molecular biology, new techniques are constantly being developed and there are certain techniques which simply become obsolete (like the pre-PCR days of cloning and amplifying genes), but with something like field ecology…well, a shovel and a bucket and a transect will always be just that, and just because you might use a GPS to mark your location, it doesn’t really change what you do all that radically which warrants you ignoring older publications.

The more papers I read, the more often I find that ideas get recycled, not that it is necessary a bad thing – we can always gain new insight on old questions by applying more up-to-date techniques. But what really irritates me is when I see an old idea recycled and the *original* source is not cited, whether they be from 1973, or from 1873.

LikeLike

This reminds me of something C.S. Lewis wrote about reading old books. Read the introduction: http://www.spurgeon.org/~phil/history/ath-inc.htm#ch_0

LikeLike

Two of my favorite classics are “Voyage of the Beagle” by Darwin and

‘Phylogeny” by Ameghino.

LikeLike

Ooh, good idea. Looking forward to reading the Chamberlain paper.

LikeLike

Chamberlain was a geologist, and a Badger, too! Bonus.

LikeLike

TC Chamberlain was required reading for my undergrad biology capstone seminar. GREAT stuff! Thanks for sharing these ideas, there is definitely more that we can learn from the information that is in all of those old PDFs!

LikeLike