A month after last January’s State of the Union Address, in which President Obama called for an increase in STEM graduates, The Atlantic published this piece on the “Ph.D Bust,” lamenting the decline in academic job placement rates for scientists. The latter has been making the rounds again, coincident with the latest William “Don’t get a PhD” Pannapacker’s piece in which he reiterates that a humanities PhD is an immense investment of time and money, and that the job prospects are prohibitively dismal. Meanwhile, says Pannapacker, we know very little about job placement rates for PhDs, (if you have a moment, please fill out your information at the PhD Placement Project), and– most tellingly, to me– Academia is doing a deplorable job in general of preparing students for “alternative careers.”

This, to me, is the crux of the matter. People call Academia a pyramid scheme; certainly, if one scholar produces as many as 20-30 PhDs in their lifetime, it’s easy to see how the numbers don’t work out in the long run. Add to that the university adjunct crisis, where half or more classes in some institutions are taught not by tenure-track faculty, but by poorly-paid, benefit-less lecturers, and it’s not a stretch to see a perfect storm brewing: too many graduates, not enough jobs, and a 10+ year investment in education and training that (as conventional wisdom goes) leaves you ill-suited for little else than those jobs that are rapidly disappearing down the drain.

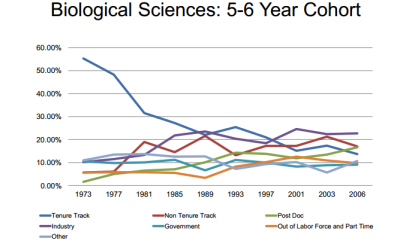

Many fewer PhDs are going into tenure-track jobs than just a few decades ago. Data from NSF; click to enlarge.

And yet, I have been increasingly dissatisfied with the broader discussion about academic job placement, and I’m finally starting to realize why. It starts with two fundamental assumptions: 1) all PhDs want to be academics, and 2) a PhD can only prepare you for a job in the Academy.

Most of the graduate students I’ve known over the years have not wanted to go into an R1-type position at a top research university (and the broader numbers bear this out). Many realized that they’d prefer to teach, write about science, or do research full-time, or go into policy. Many of these students genuinely believed that those careers were not available to them, or that they should doggedly pursue the R1 job in spite of their own doubts– a PhD, after all, is what you get for an academic job. Other folks I’ve known have become so jaded that they left academia altogether, going into business for themselves or working in some field completely unrelated to their research. These transitions can be emotionally devastating, and my friends and colleagues often express that they feel like failures, or that their PhD was an utter waste of time and energy.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with deciding that a career in academia isn’t right for you. Having a science PhD in industry, politics, education, journalism, and even business– that is, having a science PhD but not actively practicing science– should be seen as an asset, rather than a failure. Instead, it’s a failure of mentors, departments, institutions, and the broader academic culture. It’s a failure of PI’s and departments to not accept students who are interested in non-academic careers, thereby failing to normalize those choices in their labs and cohorts. It’s a failure of mentors to encourage students to discover their strengths and pursue careers that are meaningful to them, even when the students discover that those paths veer away from academic science. It’s a failure of departments to provide training for “alternative” careers that are rapidly no longer alternative at all, but the mainstream. It’s a failure of a broader academic culture that says to the general public, “we want you to value us and our work, and be informed citizens, but we don’t want to walk amongst you– we are not you.”

I’m going to go out on a limb and say we don’t need fewer PhDs, and that the PhD bust is more of an attitude problem than a practical one. We need better training. We need to better prepare students for a range of career options, both with skill-sets that can support non-academic career paths, but to show them that many of their existing skills are already invaluable. We need to train students to rebrand themselves from academics to capable problem-solvers, efficient multi-taskers, effective writers and editors, systems-level thinkers, leaders, proficient researchers, managers, communicators, and creative minds. And we need to not just provide, but require our students to learn marketable skills in teaching, programming, statistics, social media, communication, mentoring, mechanics, languages, geographic information systems, graphic design, policy documents, legal proceedings, and multimedia.

I’ve got two graduate students, an MS and a PhD, starting with me this fall, and I made it explicitly clear to them that I expect them both to acquire a complementary skill as a part of their graduate training. If you’re a PI, you can require the same of your students. Talk about this in lab meetings, and including everyone in the hierarchy from undergraduates to postdocs. Acknowledge that the job market has changed since you went to graduate school. Don’t reject an applicant simply because they don’t want to follow the path that you, Professor Hotshot in FancyPants Program at Major Research University, followed– the reality of the job and funding situation is that they probably can’t, anyway. If you’re a student, don’t despair; be proactive. Pick up skills, ask your department to do career development workshops for non-academic jobs, and learn how to rebrand yourself, and have backup plans. You may find your real dream job on the way, but at the very least you’ll be 1) better prepared with a safety net, and 2) you’ll make yourself more marketable for those precious few academic postitions.

In other words, these ideas aren’t utopian. We don’t need to fix the adjunct problem, solve institutional sexism, or restructure university administrations or political systems in order to make progress on this. We can start right now, with ourselves.

Categories: Academia Commentary Grad School

Hiring trends have changed and that’s what’s killing alternative careers in the biology field.

One of the trends in the biological sciences that affects job opportunities is a big change in hiring practices and business models. You see this in industry and also in medicine. Having a Ph.D. is now a liability if you want an industry job, as there are two things working against you. You can find an industry job with a Ph.D. IF you also did an industry post-doc. The prominent thinking in the biotech/pharma/chemistry industries is that Ph.D.’s are like overgrown children who do not know how to operate in a corporate environment, preferring to spend too much time in their own heads and not enough time trying to do something practical.

Even with an industry post-doc under your belt, the chances are slim for an industry position. They simply don’t need you. Industrial labs are filled with armies of technicians who have 2-year degrees, managed by folks with master’s degrees in the sciences. That’s the current business model since it is more cost-effective. The same trend is emerging in medicine with the PA field. Many clinics are now staffed by a platoon of PAs, a few nurses, and a bunch of CMAs, with a couple of physicians as managers/supervisors. Again, it’s simply more cost-effective.

I cannot tell you how many times I have been tempted to write to my alma mater and claim that I faked all my data so they would rescind my degree. If I only just had an M.S., the job market would be wide open to me. Instead, I have struggled for 30 years to find work in the sciences.

The bureaucracy is so thick in most institutions that getting a spot is nearly impossible. Here is an example: Two years ago, I had just been fired from a laboratory research position (because I took 4 days of vacation, which I applied for 6 weeks in advance and was part of my benefits package) at the same time that I had received a $1 million research grant from a private foundation (plus matching funds from the government, so $2 million). I wrote to departments far and wide and could not even buy my way into being a research fellow, mainly because the hands of every person with whom I spoke were tied. Think about that for a minute. Used to be, getting a professorial position was like getting an officer’s commission in the British navy: you basically bought your position with influence and money (in our case, influence, grant money, and publications). If you can’t buy yourself an academic position, even a non-tenured one, with a couple of million bucks in tow, the system is definitely broken. In the end, I had to give the money back because I had NO laboratory in which to conduct the project.

LikeLike

Hi Dr. Gill,

As you brought up the graph, the x-axis should be emphasized more. “Time” is the real miscreant here. A couple of examples to explain why. Getting a PhD in 1975 means there was no internet and the doctoral student was going to the university library to dig all the references she/ he could for literature review. Government debt in 1975 is not same as now. The number of institutions or degree programs in 1975 is not the same as now. Academic and social value of PhD (based on earning power) in 1975 and now are completely different. The number of published articles needed in 1975 and now are different and ….so on.

“institutional sexism, or restructure university administrations or political systems”, these are God’s Gift, I don’t think there will be any difference in next 100 years. But I liked that you voiced aloud.

LikeLike

I wonder how much of this Ph.D. glut is due to this seeming explosion of on-line Ph.D. programs. Historically, the selection process into doctoral programs was a significant barrier, but many on-line programs seem to accept anybody who applies.

LikeLike

Are online PhDs really that common? At least in the life science I’ve never encountered one. And programs with such low standards are not very likely to be accredited, meaning they wouldn’t be counted in official numbers of PhD graduates…

On Wed, Jun 21, 2017 at 10:17 AM, The Contemplative Mammoth wrote:

> Ryan commented: “I wonder how much of this Ph.D. glut is due to this > seeming explosion of on-line Ph.D. programs. Historically, the selection > process into doctoral programs was a significant barrier, but many on-line > programs seem to accept anybody who applies.” >

LikeLike

Nice article. Wish I had read it 20 years ago.

I think everyone agrees that most folks who have worked on a Ph.D. eventually find a job outside of academia. It also seems that many of us struggle with positively branding our Ph.D. experience. Compounding this issue is that most of the people who are advising their students have no experience outside of academia and are in a poor position to give sound advice for building a career outside of their narrowly defined research area.

No company really wants to hire someone with a Ph.D. or post-doc experience. Compared to our other entry-level colleagues we join the corporate world when we when we are a bit older, more cynical, more difficult to mold, command higher pay & have demonstrated that we are interested in our own “esoteric” research agenda. We also benefit from the assumption that we are smarter, learn quicker, and have demonstrated a deep level of dedication. If we are lucky there is a company with direct interest in our “esoteric” research topic. If we have some foresight we start or own company.

Navigating the PH.D. “alternate career” becomes a lot easier if one invests the time to create a personal brand. Clearly communicating how your passions will add value & drive increased revenue will trump the reservations that are inherent with the Ph.D. meatball. Working on your personal brand will also help mitigate the lay-off risk when sales dip.

Finding a job boils down to 3 things:

* Figuring out what you want to do

* Knowing what to say &

* Knowing who to say it to.

My academic experience offered no tools or assistance in answering the 3 basic questions for a job search. If folks in academia would like to produce highly skilled researchers who add value and increase revenue to the business world, maybe programs should add a formal career plan in addition to the current requirements: course work, qualifiers, publications & thesis. As part of a career plan the following could be considered:

* extra course work in an applied field,

* internship at a corporate research center or national lab,

* approved departures from the lab to conduct informational interviews.

A natural spin-off of this career planning would be better prepared academics as well as fewer Ph.D. students & post-docs. Highly qualified students interested in “alternative careers” would find their way sooner & may not go so far in the process before changing course. (Of course this assumes that the Ph.D. students that enter the country have status that gives them the freedom to leave academia and start working, which is a completely different topic.)

PS

I earned a PhD in experimental condensed-matter physics, worked at Los Alamos as a post-doctoral researcher and have spent the past 12 years working as an engineer. Some folks may consider my story a success. The move to industry was precipitated by my disenchantment with working on systems with no practical application. I landed a position as a new product development engineer at GE. Unfortunately the economy melted down 3 years after my switch and the short industry stint wasn’t enough to re-brand myself as a new product development guy.

Even though I am loaded up with transferable skills, figuring out how to include the research experience & Ph.D in my own personal brand is something that I still struggle with.

LikeLike

Hello, I’m interested in your idea that we can still do something from here and now. You’ve mentioned that you REQUIRE your students to acquire the marketing and branding skills. I’m interested in that part : do you train your students to acquire those skills, or do you give them time off from the research to let them attend any marketing class outside, or any others?

It seems that students not only have to do research, but also train to be marketable etc – must be like a superman because need to excel in many things. For students who are extroverts and good in planning and their research, it might be easier for them rather than introverts who are still struggling with their research and not so good in planning or even explaining him/herself. I’m interested in HOW you train etc your students, because it’s a bit late for me to train myself as I have only half year left to complete my PhD. If you don’t mind, I would really love to hear your stories / ideas regarding that.

Thank you for the post, and thank you in advance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a really good question, and as you point out, there can be costs to gaining skills that are outside of your research. I don’t think it necessarily reflects being superhuman, though. I think of it more like job training. It’s possible to gain these skills in your regular day-to-day PhD training. I think framing the situation as one where anything that’s not your project takes away from time at the bench isn’t helpful — this attitude is used to justify not taking the coffee breaks that can develop into a new project, or going to a seminar that ends up giving you a breakthrough.

Part of it is a matter of reframing. Many students are already teaching because that’s how they’re funded. You can take a little extra time to go to a pedagogy workshop or be a part of a program that gives feedback, or take a professional development class. This will have benefits regardless of what you end up doing with your PhD. Similarly, being good at coding will help your research, but it will also help you be marketable as a data scientist or consultant. Taking the time to blog creates networks in the communication field but also helps you refine your ideas, be a better writer (which is always good!) and improves your visibility, regardless of what job you pursue. You don’t need to do all of these things, but I think it’s good to 1) diversity beyond the tools you need in the immediate pursuit of a research question, and 2) to realize that you can reframe your thinking about these “extracurricular” activities, because they are ultimately helpful no matter what.

If you only have half a year left, that’s a tough time to add new skills, but it’s not your only chance. The postdoc is designed in part to help you gain skills. Start looking around for short courses, postdoc and fellowship opportunities that will allow you to develop an area you’re interested in (teaching? Policy?), and you can also take free online courses (stats and programming), read up and dive in (blogging!), or other ways to augment what you already know.

And, finally, inspired in part by your comment, this spring I’m inviting outside guests to talk to my students about their non-academic career paths during lab meeting each week. I hope that helps!

LikeLike

I love this. I’m scratching my head how to train a PHd graduate how to do work in real life applying theory to real life application. He’s one of the most toughest people I have to deal with, mostly because of the ego.How do you teach to humble down and just be open to learning new things?

LikeLike

This is tricky. Sometimes, there’s no way to get past that. Other times, you can strategically use certain milestones — a performance review? — as a reality check. Other times, it may be more appropriate to find a better fit for the PhD, like an independent or research position, maybe? Something in leadership? But as academics, we’re used to getting reviewed, and getting feedback is an important part of our process. If you explain what they need to do in a clear, written format, it may help.

LikeLike

I have to say, this article and the comment section definitely intrigues me because I’m one of those who has planned since a young age to go all the way. However, I’ve heard similar horror stories of PhD’s not being able to find a job or excel. In my own organization with more than 3500 plus people, I only know of 1 PhD and she is in a mid-level position…The CEO has a Bachelor’s level degree. I have more degrees than the CEO. I will be finishing my 2nd Masters degree in May of this year. My plan is to go towards my Doctoral degree in a couple of years once I’m able to quit my job and work my currently, side business full-time. I’ve already looked into several programs and have made my choice. I picked this program because it is not a PhD but a doctoral with a doctoral project in the end. I decided this route because I want immediate application of the program but still want the research component. Without the PhD portion, I know I won’t ever get tenure (not my plan anymore) and I won’t get offered as many teaching positions. Yes, I would like to teach but know that opportunity is smaller for non PhD doctoral level degree holders. Because I perceived that it is harder for PhD to get non-academic application in the form of a job or paid assignment, I decided this route. Why? As the author of this post said, some of us just LOVE research and going this deep into a topic that we love. My love of intense research at this level is my main reasoning…but I also want to get some type of application from it…as I can’t see myself spending so much money just because I love something, unless I’m rich…and nope…that I am not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, I have to say, even when I had my first Masters, I was told that I was over qualified for some positions. I stopped using it because as a single divorced mom, I needed a job. But I think my biggest issue was I didn’t have a lot of relevant work experience and there were people who were threatened that I had a degree. I remember going on a group job interview at Victoria’s Secret and the store manager asked for all of our resumes. Of course, I had my degrees listed. During the interview, when she was speaking to me and other candidates, she looked straight in my eyes and said, “I can assure you, I didn’t need a degree to become store manager.” I was floored. In one of my previous roles, I didn’t promote my education ahead of getting the job, so when my boss found out, she called me into her office to specifically ask me, “Why are you here?”….ummm…because I need to pay bills! Of course I didn’t tell her that. She was on a war path after that and I ended up switching departments and now work for an amazing boss who has been helping me get my corporate career off the ground. My corporate career is my Plan B, however. My Plan A is a consulting business I’ve been working on since 2011 and now it is bringing in real traction after working on it part time for 5 years.

My thoughts are this…PhD earners, just as the author suggested, have to have real life work experience. I don’t think it is a good idea to go for a PhD with no real world experience to apply it to. This makes the learning from the PhD program complete “theory” with no real world application. I almost started a doctoral degree program years ago but am glad I didn’t because now, I can be more strategic with my learning as years ago, I wouldn’t have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shun, when you say “doctoral” do you mean something like a D.Psych., DPH, or the like? Some of those professional degrees are acceptable in academia, at least for occasional teaching at career-oriented departments. (Even “just” a J.D. or an M.D. can be enough for that.) It sounds like you have thought this out but, again, remember that at least past the bachelor’s a graduate degree itself doesn’t mean too much unless it is in a field where there is a demand. Saying “I have a master’s” is not an automatic door to success. Since you have 2 already I’m sure you know this. Also, carefully choose what is in and how you develop your doctoral degree. Make your final project something relevant and establish good connections with faculty who might give you a boost afterwards. (And whatever happens don’t get between two of them if they have egos–the worst thing is to end up the football when they are both on your committee.)

LikeLike

I got here after been rejected on a PhD program just because my master’s degree doesnt seem to correlate my intended research. Isn’t the goal of doctoral studies to abroad and expand knowlegde? Amazingly the problem persists.

LikeLike

It is, but you also have to remember that you are an investment of resources. If you’re in a funded program, I need to know that you’re a good investment and will deliver. I don’t have the details of your particular situation, but I often see students applying to programs willy-nilly without taking pains to make personal connections with potential advisors and explain how their changing degree fields make sense in the broader scheme of things. I know lots of folks who got graduate degrees in fields totally different from their undergraduate or masters work. But to pull that off, you need to make sure you’re connecting with folks in your department and making a strong case.

LikeLike

The problem with the answers of many respondents is that they always emphasize the ‘creative and analytical’ skills that PhD holder possess. The premise in this line of thinking seems to be that ‘they’ are the only potentially suitable candidates for certain jobs, and nothing could be further from the truth. There are plenty, and I mean plenty of people without a Ph.D. who would be superior job candidates over many doctorate holders. In fact, those individuals have been earning loads of money at challenging, stimulating jobs for years. When it comes right down to it, working at something, rather than studying something general (save some professional jobs i.e., medicine, law, teaching, engineering) always put one in better stead in the workforce in every way. To have a Ph.D. diploma hanging on your wall just to stroke your own ego because you are a ‘doctor’, is senseless narcissism and hubris. I know a guy who got his Ph.D. in sociology who is working at Chapters. What makes more sense to me is earning an undergraduate degree first, and then a professional degree right after. This is a win-win situation, because you end up with graduate level credentials and employment in your chosen profession right after you graduate. This is one example of graduate education that makes total sense.

LikeLike

While I appreciate your comment, I’d like to push back on the idea that having a PhD means you only study something, as opposed to having practical experience in it. PhDs involve quite a lot of hands-on training, in addition to the coursework and other kinds of skill development.

It all comes down to your professional goals, and being flexible. You don’t need a PhD for many non-academic jobs, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t bring something to the table. I didn’t get a PhD to stroke my ego, I did it because I wanted deep training in a field I love. Let’s try to avoid harmful stereotypes about PhDs as being bookworms without social or professional skills.

LikeLike

Assuming you can get employment in your chosen profession “right after you graduate”. Internships might be one way of coordinating this, but i suspect at least some programs would like their students to have a little practical experience in the world before going for higher degrees.

LikeLike

Thank you for this! I have often wondered why most docs only strive to work in academia when so many other industries/venues could benefit from their immense skill sets. Perceptions can change, so get out their and start changing them! Yes! Love it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The report “SET for success: the supply of people with science, technology, engineering and mathematics skills” from 2003, also known as the “Roberts Report”, has come to similar conclusions, and has generated a lot of activity in the UK at that time. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/4511/ So, that’s an opportuntiy to see if and how your suggestions work…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Rose M. Reynolds, Ph.D. and commented:

Really interesting post on the “PhD Problem”

LikeLike

You are right.

Thank you.

review my PhD

LikeLike

I’ve got some many questions about pursuing a doctorate. I think in a few years, when my children are older, It is something I’d like to do. But it doesn’t seem feasible with a full time, WELL paying job.

LikeLike

There are definitely opportunity costs. Getting a PhD can be a gateway to a better job, but most of us do this because we love it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just found this article and wanted to ask some questions of the general variety. I am a good student and apply myself consistently to my school work. I have a GOOD job that pays well enough so that my wife doesn’t have to work and she can take care of my two children. But I’m not satisfied with what I do and want to pursue more education. I know I want to get my masters, but I have recently thought about obtaining my doctorate, but I’ve no intention of staying within academia. Is it reasonable to assume that I can accomplish this goal? I’m leery of the work load a doctorate program would impose on me with my other commitments, and whether or not a school would accept the application with my extenuating circumstances.

Wish I was more focused in my youth, but I’m running up against my mid 30’s and know that eventually I’ll want to expand my academic credentials.

LikeLike

I think it depends a bit on what you want to do. I think it’s difficult, though not impossible, to do a PhD while working another job. A PhD is a full-time job and more. If you have the flexibility of your wife being able to work while you’re in school, that would be one option. You’re right that there would be red flags in your application if it were perceived that you couldn’t devote yourself 100% to your schoolwork. Remember that schools see you as an investment– they have lots of applicants and not a lot of resources.

Lots and lots of people don’t end up going to grad school until their late 20’s, 30’s, or even 40’s (or beyond). It’s definitely not uncommon! You’ll just have to figure out a way to make it work. It may mean some lifestyle choices, but I have seen lots of people with similar circumstances to you successfully get a PhD.

LikeLike

One must be careful with appeals to industrial applicability. Schools are always 50 years behind industry, but what boggles the mind is that people treat academia as if it were a trade school. It isn’t. Now, clearly, if you major in philosophy (and I mean, the real stuff, not the postmodern/masturubatory garbage you see these days), it can benefit your greatly by developing your intellectual abilities which have can cultivate intellectual independence and dexterity which translates into effectiveness in all other activities requiring some some brain (most majoring in philosophy, like most majors, don’t actually reap much, esp. not those in postmodern/masturbatory/navel-gazing/pseudo-intellectual/pompous departments). However, don’t be surprised if all employers don’t jump at the chance to hire you when they see “Ph.D Philosophy” on your CV, especially when you haven’t got any other major with unambiguous industrial presence. Not everyone has the appreciation of these fields for what they are. However, we can’t blame industry entirely either because the poor opinion of the humanities today, if overgeneralized, is often largely deserved. Stupidity is perpetually epidemic in human populations, whether it be academia or industry. Its presence in academia is, however, particular irritating because in a place where individualism and virtue are particularly necessary to carry out genuine intellectual work instead of engaging in arrogance, subservience, mutual admiration, peurile masters-o’-the-universe delusion, or pompous bullsmithing. Academia should know its place. It isn’t the center of the world. And frankly, it’s far too easy to sustain bullshit at universities when they remain largely immune to market forces.

Frankly, too many people go to universities in the first place.

LikeLike

“Schools are always 50 years behind industry” may be true in a handful of cases but is false and if anything reversed in the life sciences, where industry continues to depend on having a pipeline of drug targets and an ever-expanding set of techniques from academic research. (I’m also not sure what the relevant point of comparison in “industry” is for philosophy.)

LikeLike

I don’t know about 50 years, but professors may often be the last to know what is going on in the job market. Talk to people actually working in the field you want to be in. What skills were valuable (both academic and non-academic)? What were the surprises? What didn’t they need (yet)? What is the culture like in the real world (and at various places)? This is important; you can have all the knowledge in the world, but if you can’t apply it then it is only “nice to have.”

LikeLike

Please visit http://aftermyphd.com for career advice and information about alternative careers for PhD graduates.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for this! I hope folks find it helpful.

LikeLike

You are welcome! Please also check out our newest article on the top five tips to improve your CV to boost your exposure outside academia: http://aftermyphd.com/improve-cv-outside-academia/ – Feel free to comment on the comments section and like us on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/aftermyphd) and follow our news on twitter @aftermyphd

Your AftermyPhD Team.

LikeLike

I am so very glad I ran across your article. Having just completed a Masters degree, I was caught in the dilemma of, not what to do next, but the “how to do it.” Meeting with one of my professors recently brought up some very basic questions I needed to be prepared to answer for myself. I returned to school after many years (decades) away from academia. My department, upon my acceptance, indicated that I was “provisionally” accepted. I heard not another word from them, except a resounding “congratulations” when I graduated this past May. Goal accomplished. Now what? I’ll be retiring from my profession of 25 years next March. What to do? His very simple remark, after a short and concise description of my “vision,” was, “Applications are being accepted now. Apply!” I knew what he was saying … “Go get your Ph.D.!” Really? So, i am now perusing the net, looking for viable programs that may admit me, a flagrant “senior” and undoubtedly qualified (I believe). I’ll do this, too … piled upon years of skills, knowledge, tools, and gifts, all seemingly unrelated, but all invaluable unto themselves. Thank you, thank you, and thanks for invaluable validation for living the life I want to live, and doing the things I must continue to do ….

LikeLike

This is a response to an earlier comment made on August 15. As someone who has left academia, as indicated by my comment that my advisors had “cut ties with me,” I have applied to corporations, non-profit organizations and tellingly enough, admin positions at universities–all of which have rejected me. And if you are not sure about these statistics, check out the profiles at your own universities and see how many of them are occupied by people with Ph.ds. It is not a hard statistic to find–it just takes time to amass the data by searching the profile on each worker. The writer of this blog claims that “there are no statistics out there,” while dismissing the ACTUAL lived experiences of those who have gone out there and found nothing. If you are a social scientist, you must realize this is data even if it does not come in the form of a percentage. Even if the university does not have more quantitative studies on hand, perhaps we should not blame the victim by telling them to have gone into a “better field,” but ask the deeper, more compelling question of why is this employment information not more readily available, particularly as this adjunct employment crisis has been going on for the last twenty years? Why are the universities only now starting to worry about what will be the fate of their graduates? Is it because universities actually care or is it because they are worried about the future of graduate enrollment? And if MOST are not going to get a job in academia, wouldn’t it be better if they weren’t taught by professors but by someone else? These are questions that fall outside of the typical reskilling argument yet important questions nonetheless.

LikeLike

I’m not dismissing your experiences as “not data” or mot important. Please don’t misrepresent my words! The problem is, I have lots of colleagues whose experiences were the polar opposite of yours. Those examples don’t negate your experiences any more than yours negates theirs. Pannapacker also called for data on this in his post– in fact, that’s why I cited him in the first place. It certainly wouldn’t hurt!

Professors can and have trained folks for non-academic jobs quite successfully in many fields– look at med school, journalism, teacher training, law school, GIScience, veterinary school, business school, and other models.

I wish you the best of luck with your job search. I’m sorry that the culture of academia is such that your advisors let you down by cutting ties– that’s the attitude problem I’m talking about. In my graduate department in Geography, many, if not most, students ended up going into a non-academic jobs (USGS, journalism, non-profit work), and that kind of behavior wasn’t at all the norm. It doesn’t have to be: that’s my point. People have bad experiences everywhere, but there are also good ones. In the meantime, we can do a lot to make sure more future students have good experiences than bad.

LikeLike

There may not be more statistics because the results would be too depressing. I got a doctorate in geography and topped out at $49k at a for-profit college; 18 years later and with 4 degrees, but that’s what the market would bear. (Was on a tenure track at a real school but didn’t get far, which was more me than the field. But there sure weren’t any other offers in or out of academia, so after 7 years of temp work I took what I could find. But then today “real” academia seems to be increasingly staffed with adjuncts. I am teaching math and physics at a university–get 3-4 classes a year, which is typical of the place, but even that is declining as the enrollment drops in sync with rising tuition.)

I will say that a Ph.D. is personally satisfying, and does get you a better class of rejection letters. Combine a social/humanities degree with some “practical” area like law, IT, a physical science, or business and you might have some credibility outside of academia. Or not. Good luck, Wendy. There are a lot of people like you out there and, as attendance in traditional college programs is increasingly questioned, this topic is being recognized. It’s too bad things have come to this–an educated population with good exposure to humanities and social sciences is an informed population. But perhaps that’s not where the country is going anymore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an interesting blog, and useful to see the US perspective on a problem faced in the UK, but not to the same extent. There is a similar issues in the UK, i.e. obviously fewer academic positions than PhDs and a bottle-neck that appears between post-doc and tenured positions. I think we are more relaxed about PhD and even post-docs going into jobs outside of academia, particularly into industry where PhD level training is valued in R&D departments. What is less clear is how you step out after a PhD or a post-doc into a non-academic position. Even in the current economic climate there are plenty of job opportunities- in anything from business, industry, science communication and policy and elsewhere. But as highlighted in Jacquelyn’s blog, there is not enough support and advice given to PhD students about how to make sure you have the right experience to apply for these types of jobs. It often requires plenty of self-motivation and voluntary work outside your core research time to do this (if you have the time, that is).

I work in a chemistry department at a British university. Some of my friends and colleagues decided that they wanted to find out about jobs opportunities outside of academia, so they organised a Career’s event. We had people from industry, science policy, patent law, teaching and even a serial entrepreneur, all with chemistry PhDs behind them, come and talk. More info here

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on lava kafle kathmandu nepal <a href="https://plus.google.com/102726194262702292606" rel="publisher">Google+</a>.

LikeLike

Very glad that you and others are noticing the attitude problem. I’m part of a cohort of science grad students at UC Berkeley trying to draw attention to this very thing, and we’re asking the university to step up and offer career and professional development services to PhD students. Better employment means higher alumni satisfaction and stronger relationships with industry. There’s only so much that an individual student can do without institutional support, but hopefully with enough student voices speaking collectively, universities will start to pay attention.

LikeLike

That sounds like a fantastic initiative. I wish you luck, and I would love to hear what you find. It could be a model for other programs.

LikeLike

Thank you! Some universities do a lot already–Stanford and UCSF are two local examples. The problem is that most schools don’t have access to that level of cash to provide resources, and we can’t exactly guarantee that career development is a solid long term investment (though I truly believe that it is). I feel like the best compromise will be a program where students supply most of the labor through volunteer organizing, and the university just has to chip in a little bit of administrative know-how to publicize events, keep in touch with alumni, etc.

LikeLike

Great opiate for the masses.

I agree with what one of the other commenters said about how it is an enormous inefficiency for someone to go most or all of the way through a PhD before figuring out that they are unlikely to get a tenure-track job and that they need to find an alternative career. I seriously doubt that most applicants to PhD programs have any idea what they’re getting themselves into. Even if they do, they naively think they’ll be the exception to the rule.

And great, so maybe 10% of the time I spent during my PhD got me to a modest level of proficiency with an employable skill… and I’ll have to go out on the job market and compete with people who have mastered that skill in a more appropriate training program. Take programming (your suggestion) as just one example. It would be foolish to think that the programming skills of *anyone* with a PhD in ecology would stack up against those of a newly minted computer science BS, of which there are a dime a dozen applying for programming jobs.

The bottom line though is that people in PhD programs are trained to perform original research on some incredibly narrow topic and to do so in a way that sets them up for an academic career. That is great for the lucky few who can actually attain that career, but for the rest of us it’s a terrible waste of time once we gain the hard-won hindsight to realize as much. For someone like yourself who is about to embark on a career of setting people up for failure in life… I mean training PhD students… perhaps you should do the decent thing and dissuade people from an academic career path before it’s too late. In the absence of PhD students, you can fuel your research program with postdocs; there will not be a shortage of them anytime soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your comment suggests that you didn’t read my post very carefully. Especially the parts when I said that 1)I would take graduate students regardless of whether they wanted to go on to academic jobs, 2)I would require all of my students to gain a marketable skills, 3) I think we should be preparing students for and validating alternative careers, and 4) that there is nothing wrong with people who want to pursue non-academic alternatives.

As for our research only preparing us for a narrow field, that’s a bit of a spurious argument. Graduate students have to go through extensive education and qualifying exams in a number of subjects, in order to display competency to teach in those subjects. The majority of us IN academia don’t teach courses only specific to our field of study– rather, general biology, chemistry, history, or other courses that are a part of our broader training.

Your example of an ecologist competing with computer scientists is an interesting one. I would argue that there are things an ecologist knows about ecological data and statistics that make them much more suited than computer programmers for jobs in, say, the National Park Service, the Forest Service, various NGOs, environmental consulting firms, zoos, national laboratories, the forestry/rangeland/agriculture/aquaculture/permaculture industries, science communication and/or journalism, the USGS, museums, or landscape architecture. To name a few.

LikeLike

Rather than accept those students at all and mentor them as you have described, why not save everyone time and effort by saying something like “no really, you’ll regret this in a few years” or “then get a masters in computer science, not paleoecology”? The only person’s interests who they’ll serve otherwise are yours, by furthering your career at the peril of their own.

For each of these alternative career outlets you list, it should again be noted that there are people with specific training in all of them. Forest Service? Lots of universities have forestry majors. Likewise for landscape architecture, agriculture, etc etc. So what value does Suzie Q’s background in paleo- this or that, community phylogenetics, or some other esoteric topic present for government agencies, NGOs, or businesses compared to someone whose background is more relevant and appropriately specialized? There is an argument to be made for a liberal arts education and all that, but that argument becomes a little ridiculous beyond the undergraduate level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to respond to the last paragraph above. It is almost a reflex that people will mention — over and over — possible careers in “science journalism” and museums, zoos, etc. There are essentially no jobs there, trust me. A close relative of mine has a Ph.D. and has been trying for years to make a living as a science journalist, writer, and editor. She is still a part-time freelancer and only can add very modestly to her family’s income — even though she is a fantastic writer and editor. Science journalism is a tiny field and NOT easy to get into, even if you do it for years. Museums are even worse. Any number of elite-university professors who hate teaching would love to get a museum job. Environmental consulting firms are looking for people with broad and practical training in environmental science per se, including lots of geology and chemistry, not just ecology in general — most have a very focused bachelor’s degree with practical training in permitting and environmental regulations. National laboratories? Again, the level of competition there is beyond elite, and their needs are very specific. “Various NGOs” — again, very stiff competition, though not quite as bad as the aforementioned alleged possibilities. The person who posted the comment above is right that many bachelor’s degrees provide broader and more useful training than most PhDs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I pointed out in the link to William Pannapacker’s piece, we actually have very poor data on job placement. I have just as much anecdata as you do that suggests otherwise. Until we know actual job placement rates of PhD students outside of academia, saying “there are essentially no jobs there, trust me” isn’t helpful. I know plenty of people who have gotten jobs in all of the fields I mentioned. And, certainly, if folks with higher degrees are having a difficult time getting jobs, that merely reinforces my points about marketable skills and branding.

LikeLike

Here are your data: http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/career_magazine/previous_issues/articles/2013_07_24/caredit.a1300150

LikeLike

After sending out 10 different job applications a week for the last year, all I have been able to secure is part-time employment. The various “good people” at university who encouraged me to continue with my Ph.d. have now cut ties. The academy DOES suffer from an attitude problem and the biggest one is that they refuse to clean up the mess they have made. There are statistics on placement rates from the UK and Canada (see MacCleans) and they are abysmal. Even the universities refuse to hire them. Please stop trying to prop up a corrupt system which values profit above all else. If you truly want to know what a Ph.d. is worth, trying leaving academia and see what you can get for your degree on the market. I think once you realize how truly dire the situation is, you will come to the conclusion that there are far less costly alternatives than graduate education. Getting people to sacrifice large chunks of their lives for dubious rewards is not only incredibly self-serving, it is also a form of fraud. Full professors know this cruel reality (in fact, they actively dissuade their own children from going into academia) but don’t advertise to prospective grad students. I hate to open your eyes in such a harsh way. Mine are opened every time I think of how little I will have saved for retirement as a result of my years spent in the academy.

LikeLike

I don’t know the specifics of your particular case, and it’s very difficult to comment on, but if those job applications were all academic positions, I’d have to go with The Professor Is In and suggest that it’s time for a reassessment of your application package. I’ve seen the placement rate statistics– including for the US. I was quite explicit about the fact that most PhD’s aren’t going to get an academic job — did you read the post?

I also want to point out (for the benefit of those reading) that you’re making some very strong, sweeping statements that aren’t backed up by evidence (e.g., “full professors dissuade their own children from going into academia”). Hyperbole doesn’t help anyone prepare, and it’s honestly beside the point: I specifically stated that most students aren’t going to go into academic jobs. As for cost, I would certainly urge any student to avoid graduate school if they had to pay for it.

I’m not trying to prop up the university system, and I’m quite confused by you and other commenters that suggest that I’m defending it. This post is clearly critical of universities! I’m genuinely sorry for your situation, but if anything I think it proves my point, because if you’d had better preparation for non-academic “alternatives,” you might have found a better time on the market. It certainly can’t have hurt.

LikeLike

Replying here, because there’s a limit to the in-thread responses below.

“Rather than accept those students at all and mentor them as you have described, why not save everyone time and effort by saying something like “no really, you’ll regret this in a few years” or “then get a masters in computer science, not paleoecology”? The only person’s interests who they’ll serve otherwise are yours, by furthering your career at the peril of their own.”

Because that’s simply not true. As a case in point, I look at my graduate advisor, whose advisees have gone on to teach in public universities, to work in labs doing agriculture-related research, to work for a science non-profit (including publishing reports on a geoscience workforce shortage, I may add), or a conservation research non-profit, or to work for National Geographic. None of his advisees have failed to get a job of one kind or another where their training was an asset. Because, contrary to your opinions to the contrary, higher education and training is necessary for many jobs, academic or otherwise.

“So what value does Suzie Q’s background in paleo- this or that, community phylogenetics, or some other esoteric topic present for government agencies, NGOs, or businesses compared to someone whose background is more relevant and appropriately specialized? There is an argument to be made for a liberal arts education and all that, but that argument becomes a little ridiculous beyond the undergraduate level.”

Well, first of all, these topics aren’t necessarily esoteric. There may be methods or levels of detail that aren’t going to be understood by the general public, but that doesn’t mean that the subjects aren’t of interest, when framed accessibly and compellingly.

As for relevance, backgrounds in paleoecology or community phylogenetics or what-have-you are valued beyond academic careers. From your comment, you may be surprised that there are in fact government and NGO jobs where those backgrounds are valuable in their own right– I listed a number of them, but I’ll do it again: US Geological Survey, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Fish & Wildlife, National Park Service, Union of Concerned Scientists, Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Federation, Smithsonian Institue, National Geographic. Other times, it’s not so much the specific background (e.g., the dissertation) that matters as it is the broader training and skill set, such as with science writing, working in university administration, working for the insurance industry or an environmental consulting firm, making maps for the New York Times, helping run an environmental summer camp, or being a park ranger (I know people who do all of those things with their advanced degrees).

If you genuinely don’t have a good understanding of what you can do with advanced degrees outside of academic teaching and research positions, then that’s something you share with many students who start to decide that academia is not for them. And now, we arrive back at the point of my post: those jobs exist, and we can be valuable candidates for them with a little foresight and institutional support. There are a number of people who have commented on this post already that are in successful non-academic careers where they apply their scientific training. So before you accuse me of exploiting my students (both of which, I might add, have expressed interest in non-academic careers), you might want to consider the fact that those jobs exist but that you’re just not aware of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A senior executive of a government agency once told me that he valued potential employees with strong backgrounds in quantitative ecology, particularly those with PhDs. He wasn’t interested in their particular research expertise or knowledge. He wanted their analytical minds for his government agency. He thought doing a PhD in my research area helped foster those minds in ways that simply working for the government agency for the same length of time would not.

LikeLike

I have a PhD in oceanography, haven’t quite settled in a permanent position either inside academia or outside academia, and it actually doesn’t matter to me that which of those it ends up being. I currently work very closely with people in academia (as well as outside) and use the knowledge and skills from my PhD/postdoc every day.

Getting a PhD to me meant that I would put myself in a postion to be a leader no matter what field, subfield or organization I would eventually work in. I developed the PhD skill set (discussed in this post and in the comments) by pursing a PhD; skills that I believe not everyone necessarily desires to develop (nor should they). So, I’m counting on that skill set to give me the credentials and credibility to eventually take on a leadership position in a government agency, an NGO, as an entrepreneur or as the PI of a university-based research lab. I’m not sure yet which route will offer me the best chance to impact my field in the way that I want to.

The key part that is important to me is that I have more control over my job (and I believe, my happiness) now than if I had ended my education with an undergraduate degree. Sure, there are fewer jobs available to people with PhDs (it makes sense), but I know that I personally would not be happy with any of the “easier to obtain” jobs that require an undergrad or master’s degree.

I would encourage students who show leadership, vision, self-motivation, and scholarship to pursue the highest degree possible in their field of interest. I think it’s a win-win for the student and PI.

LikeLike

Yes, the jobs EXIST. There are also far, far more PhDs than could ever be accommodated by the very, very few relevant jobs that EXIST, and there are also people who are better-qualified for those jobs. The latter persons will also not get slapped with the irreversible, career-killing “overqualified” label which prevents one from getting that critical entry-level job in a given field. It’s hard for me to believe that you are an educated person, have a Ph.D. in fact, and yet you seem to think that the fact that you know a few people with PhDs who have such jobs, means that it is realistic to hope for such a job with a PhD. This is fundamentally a quantitative issue that has to do with probability. Yes, there are people who have won the lottery. Some of us may even know them as friends. That doesn’t mean that buying lottery tickets is a good idea. If your PhD students have expressed interest in non-academic careers, great! But that doesn’t mean that hiring managers will express interest in them, especially if they don’t have practical work experience IN that same field BEFORE they embarked on their PhDs, which is the only way to (potentiallly) avoid being labeled an “overqualified,” hopeless academic egghead.

LikeLike

You obviously have strong feelings about this, which is fine. It’s not okay to break out the ad hominem attacks. You’ve been warned.

I pointed out in this post that there is not clear data on PhD job placement. So, in one comment, you use anecdotes about people you know, and then in this comment hold me accountable for doing the same? Obviously this is my opinion — I’m very clear on that — and it’s based on my experiences. Your experiences are different, which is why we need more data. Until you can show me the data on how many “relevant” jobs there are, versus the number of applicants, then you don’t get to lecture me about whether this is a quantitative or qualitative discussion. In the meantime, there is absolutely no harm in requiring students to have marketable skills (and experience! You seem to have a misconception that you can’t get relevant work experience in graduate school, which is patently wrong), and preparing them for the job market as it exists, as opposed to what we’d like it to be.

There are droves of BA and BS holders who are moving back in with their parents because they can’t find jobs, either– that’s hardly Academia’s fault. In the meantime, you could just as easily attribute lack of hiring to the very attitude problems I talk about. Plenty of people go to graduate school precisely because they need higher degrees to excel in their non-academic position– you admit that yourself.

This post is not an argument to get a PhD. This post is an argument to better serve and prepare the students who are on their way to getting one. I’m not interested in an argument about whether higher degrees are useful, or valuable. I am interested in making sure that we are doing our absolute best to prepare students for meaningful careers. The job market will always be competitive– that’s true of any position, whether it’s in business, academia, or food service. There will always be more applicants for a given job than there are positions. Not all career paths will be easy, or possible for all people. But in dire academic times, it hurts absolutely no one to think strategically about your career options, and to demand better training and support.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a PhD and I work in industry so my job is not academic but I am doing the same field of work. Instead of doing new basic research I am bringing research to the practical application. Which is actually a weak point,. There is lots of great research that doesn’t make it out to the market. Filling this gap is how I view my role.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post Jacquelyn, and great comment Karl! That is my situation now too, working in industry (http://dusk.geo.orst.edu/compass.html)

LikeLike

I see I’m very late to this (sorry! traveling!), but I just wanted to add that over at Dynamic Ecology we’re doing an ongoing series of guest posts on non-academic career tracks for ecologists. The most recent post in the series is here: http://dynamicecology.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/advice-finding-a-career-in-non-academic-research-guest-post/

And apologies if someone’s plugged this already, but at the Ecological Society of America meeting in August there’s a panel session on non-academic career tracks for ecologists: http://eco.confex.com/eco/2013/webprogrampreliminary/Session9083.html

LikeLike

Really enjoyed reading this article. I agree with the author that majority of PhD graduate no longer becomes professors. In fact, I have done some research which suggests the same. It is shown in my blog:

http://controlgradstudy.blogspot.ca/2013/06/phds-and-job-market.html

However, I am not sure about if we need more or less PhD. The problem is we don’t really know how much appetite does industries have for hiring PhD. If we said we wanted to increase more PhD and industries just don’t have room for it, there will be serious consequences. Having less PhD will reduce the rate at which technology is progressing. A fine balance must be sought.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m curious – do you have or know of any syllabi for good alternatives-to-a-career-in-academia seminars? Or, heck, a general professional-training seminar where 1 week is on the TT life, but the rest covers other options? It would be a huge boon, particularly bringing in guest speakers.

LikeLike

I wish! That is an awesome question. We should start collecting links. I didn’t ever really have any of that kind of training, or seek it out personally, so I don’t have those resources. As a PI, I’d love to have them. Alternative careers should really be a part of professional development seminars.

LikeLike

I almost wonder – if we put out a call on Twitter for careers folk think should be covered and folk who would be interested in being speakers if we couldn’t put together a kickass syllabus/contact list…maybe on Monday?

LikeLike

I was thinking that would be a great idea! Let’s make it happen. I can collect the responses in a Storify and post as a follow-up.

LikeLike

I would love to participate. I have a Human Genetics PhD and now work as a Senior Education Policy Analyst at a national nonprofit organization. In the interim, I was a science writer, curriculum developer, and educator professional development provider. I’d love to share my story.

LikeLike

Have you seen this, which Jane Catford (http://janecatford.wordpress.com/) just forwarded to my group? A list of “Career Resources for Non-Academics” from the Earth Science Women’s Network:

http://eswnonline.org/career-resources/nonacademic/

LikeLike

The numbers don’t lie. “Alternative” careers are becoming the norm for PhDs. There just aren’t enough tenure-track academic positions to go around. We really need to align graduate training with the realities of the job market.

Training for non-academic careers should be part of the graduate school experience. To do this effectively, departments and universities should consider forming partnerships with other career areas (industry, journalism, education, etc.). This would provide tailored mentoring to grad students interested in non-academic careers, which may relieve the burden on faculty. It’s a lot to ask of faculty to provide expert career advice on whole industries outside their realm of experience. Building partnerships with professionals from these industries can benefit grad students and may also help faculty understand the opportunities and challenges of the wider job market.

LikeLike

Wow. If you are getting an advanced degree in the biological sciences, and this article and discussion really speaks to you (I am sure that there has to be a lot of non-academic employment opportunities in the bio-medical arenas), switch to a food science degree, department, and focus. The actual science work will be similar or aligned to that being conducted for other biological sciences degree, but the whole area and discipline is supported by the largest industry in the US and world – food. Industry – production, R&D, safety, business, etc – government, policy, IT, international opportunities, basically most of what the author listed near the end of her article, are part of the structure and broader learning experience of the undergraduate and graduate food science degrees and program.

LikeLike

I think you make an excellent point. At UNH we’ve had a number of PhDs go into industry or policy but mostly in fisheries and climate science (from natural resources and ecology fields).

However, I wonder if a phd is the best way to get the desired skills for most jobs outside academia? Is it better to get a masters then work your way up through the ranks in industry (or government), getting appropriate skills along the way?

Also given how science gets done, there are a lot of incentive to push students to work as glorified technicians and publish as much as possible at the cost of developing other skills. I guess students should just look for more progressive advisors. I applause you for helping your students in this way and for raising these issues.

I get very negative at times about the myriad of issues you mentioned at then end, so it was very uplifting to hear a reasonable solution that doesn’t require changing the entire system.

LikeLike

Yes, it absolutely is better to get a bachelor’s or at most a master’s degree, then start to work your way up, IN the industry. Only after at least a few years’ full-time, professional, relevant work experience should you take a break to pursue a PhD. The kiss of death is a PhD without any relevant non-academic work experience. You’ll be older when you finish, but you’ll have options.

LikeLike

“Kiss of death” is an overstatement. We actually don’t have good data on this, but my point (if you’ve read this post at all) is that it needn’t be a kiss of death if you get relevant non-academic experience.

LikeLike

This really varies field to field. How would a PhD in theoretical physics or comparative literature go about applying those skills in industry? (Sure, they’re hard-working problem solvers… and they were before they got their PhDs, too.) While somebody working in biomed or chemistry might have an easy time of it.

Once during my PhD it looked like I’d need to pursue a different career path. So I went to the career office at my large, well-known state school. They were completely unhelpful. I don’t think the tenured/tenure-track faculty necessarily look down on careers outside academia (some do, but many don’t). They just have no idea how those careers work, and the university career offices aren’t much help for grad students. My professors simply couldn’t have given me helpful advice or training on other careers.

In physics and astronomy, at least, most PhDs do a postdoc. Or two. Or three. So they’re in their 30s, maybe even 40s, by the time they have to switch careers to industry. That’s not easy.

We do have a PhD overproduction problem, in most fields. We have people spending 10-15 years in very low-earning positions just to have to change fields as they approach middle age, going into an industry they could have gone into straight from undergrad. How is that not a problem?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree about academics often not knowing much about outside work. At least that has been my experience. And what they do know is often decades out of date. After all, many academics only talk to other teachers. But few teachers want to admit they are training people for non-existent careers.

LikeLike

I liked this article too. I think about this a lot since the probability of getting an academic job is so low. It seems like everyone in my department always talks about the lack of academic positions, talking about non-academic jobs still seems taboo.

I’m curious,in what ways are you encouraging your students to “brand” themselves? What complementary skills do you recommend them to pursue or which ones have they chosen to develop?

LikeLike

Thanks!

I give a few examples of thinking about rebranding (e.g., systems-level thinker), but basically the idea is to really think in terms of your skill-sets. I recommend Randy Olsen’s Don’t Be Such A Scientist as a way to think more about what branding means. It’s designed for scientists, but I think it can help people overcome their discomfort with the concecpt of branding more generally. As for complementary skills, I list a number of those at the bottom of the post (e.g., geographic information systems, coding, social media)– I’d pick a couple that match your strengths and interests, and really develop those.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This topic reminds me of the recent paper in Conservation Biology about how graduate students can gain skills that are useful beyond academia. Students (and their advisors!!!) should be more aware of this. Our lab group discussed it in reading group. It is particularly focused on conservation biology, but the skills cross sectors:

http://qaeco.com/2012/11/19/so-you-want-a-job-that-lets-you-save-the-world/

Also, this topic relates to the value of PhD graduates becoming teachers, particularly in the sciences:

http://theconversation.com/inspiring-science-fast-track-phd-graduates-into-teaching-14993

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Of Feathers, Fur and Scales and commented:

Please read this article on PhDs and the job market! It fits right into where I am in life right now…

LikeLike

Yup, thanks!

LikeLike

When I was earning my PhD and expressed to my advisor an interest in possibly using it to work for a conservation organization overseas, he dismissively said to me, “Oh, so instead of getting on the tenure track, you just want to wander around and collect rhinoceros shit.” Guess that hasn’t changed much since then?

LikeLike

Had my PhD advisor said such a thing, he’d have probably added, “Sounds like a good idea to me!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like this discussion because it provokes some deep thoughts about our “system”. However, it fails to address that the academic incentives for PIs encourage them to generate more PIs, as that brings them more papers and more grant funding. As a young PI, I have done just that for my former advisors. Note: none of my recent PhDs have earned their keep in this regard, despite being in academic research settings! 😉

So no, I’m afraid that until the incentive structure is changed, this problem will not go away. Young and idealistic PIs can coach their students towards alternative pathways, but if such placements are not valued by the promotion and tenure process as highly as additional pubs and funding, then it’s a doomed exercise, one that could put that young, idealistic PI at a distinct disadvantage in his/her career progression.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t necessarily think one has to follow the other. Many students leave labs after graduating and never go on to R1 academic jobs; that’s not new. What’s new is the idea that they should be getting support to be successful, regardless of the outcome. Even after a student leaves a lab and goes on to be a PI of their own, there’s not necessarily an infinite number of papers that come out of that initial collaboration. I may be a young, idealistic PI, but I plan to hold my students responsible for following through on publishing any data they collect, regardless of their ultimate career path. Certainly, with a couple of fruitful collaborations, enough papers and subsequent grants should emerge that the system could be sustainable (at least, more sustainable than it’s been).

Obviously we need to promote systematic changes; but my point was that even in the absence of those changes, we can still make progress! And, of course, as a pre-PI myself, who knows what my thoughts will be in seven years?

LikeLike

Kim makes a good point that the incentives of even an open-minded PI and a grad student looking outside of R1 academia are misaligned. Although I was explicit with my advisor that I had no interest in R1 from the get-go, I reached my highest point of productivity just before graduating (part of this has to do with working in paleoclimate – those datasets take a long time to generate, so every new published record has a long lead time). Had I gone on to an academic job, there would be more publications in the works with my advisor’s name on them. As it is, the business world is somewhat less enthusiastic about results getting published in a timely fashion. My advisor is established enough that this is not a crushing blow, but clearly it would have been more beneficial to him if I had stayed.

On the other hand, the business world is in desperate need of people with a PhD-level expertise. I am the only geologist in a company that focuses on modeling natural catastrophes – I’m good at the climate problems, but it sure wouldn’t hurt to have a seismologist or a hydrologist on staff. In the few months that I’ve been out in the real world, I’ve run across crop insurers with no climate scientists or meteorologists, predictive modelers with no statisticians, and earthquake modeling companies with no geologists (having to explain during a sales pitch that the map that says “Quaternary clastics” means that whatever building is sitting there is probably toast in an earthquake is….concerning).

Here’s the thing – the people on the business side are trying to hire people with research backgrounds, but they get lost in the shuffle on sites like Indeed or Monster, or they network with other people in the business world who don’t know many PhD folks (due to the traditional shunning of industry by PhD grads) – so they get no bites from people with the right expertise. PhD students search for jobs in academic or professional society publications, or sites like phds.org, which are dominated by academic positions, so they think that’s all that’s out there. Solve this mismatch, and a lot of the “PhD jobs crisis” gets solved too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah. There aren’t so many working in this space between academic and the world beyond. Huge potential there!

LikeLike

That is a really interesting conflict you bring up at the end. I wonder how we can start trying to make those matches between employers and PhD students, who currently don’t know where to look for each other. (As a current student who’s having trouble even figuring out where my background could fit into an industrial setting, I really do want to figure this out!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now that I’ve been in academia almost 9 years, I have to say that part of the issue is that graduate students rarely really know what they want when they start, I know I certainly didn’t. At 24, I just thought “Hey I like research, why not get a PhD, and being a professor sounds cool, can’t be that bad of a job.” It was only until I was pretty far in that I began to contemplate the future and what my career options were. It seems like a great inefficiency in the system to have a glut of PhD’s back pedal into different careers. It’s awesome if a student comes to you and says “Science writing is what I want to do, but I want a PhD.”. I’d imagine a more likely scenario is “Oh shit, I need a job, and I love to write, so maybe I should explore this path.” Are they hurt by having a PhD? No, but it seems like they might be better served having started that way from the get go. I feel the same way about myself, I probably would have been much better off having gone into a datascience type graduate program, than reaching essentially that through the very circuitous route of getting a PhD in ecology. But it’s the path I took, so I’m trying to make the most of it.

Your post though I think is a bit paradoxical. You write: “…that the PhD bust is more of an attitude problem than a practical one. We need better training. We need to better prepare students for a range of career options, both with skill-sets that can support non-academic career paths, but to show them that many of their existing skills are already invaluable. ” But that better training for other career paths fundamentally changes the nature of what a PhD is I would argue. Then it’s moving away from deep scholarly knowledge to essentially an advanced technical degree. Every hour you spend learning alternative skills comes at the cost of your science. I know that’s what happened to me, I became way more interested in data analysis, stats and programming than I was in doing ecology, and that’s why people go to my friends for ecology questions and me for stats ones. It’s why I have a career outside instead of inside the academy. So I think the question is can we “have it all”. That is have the deep training that prepares you for academia and the back-up plan? I guess I’m not totally sure that we can.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I disagree– I don’t think it has to be that way, necessarily. I think it’s useful to think in terms of complementary skills, and also recognizing how the skills you already have can be applied in non-academic settings. As an example, I’m trained as a scientist, in every classic sense of the word, but I also picked up social media skills, and I’m a good presenter, and a strong writer. The latter are not necessarily “classic” skills, but they’re ones that I cultivated. They help me in my academic career, but they’d also come in handy in other settings, like a museum outreach coordinator. I made a point of teaching, too, to bolster that part of my CV. You’re right that we can’t do it all, but we can at least be trying to actively pick up an additional skill or two, while still valuing scientific training as it exists, without having to change it to be something else. Analytical thinking, understanding uncertainty, being familiar with the process of science and the inner workings of academia– all of these, too, can come in handy in alternative career scenarios.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course many of the skills acquired as a PhD are applicable to other fields, but I still agree with Ted Hart that the very structure of the PhD teaches people the skills most applicable to academia… and the PhD is not the most straightforward way to prepare oneself for an advanced career outside of academia.

I also pretty much disagree with the central thesis of this article.. I don’t think most PhD graduates have an attitude problem seeking non-academic jobs if that’s what they’re interested in, or if they cannot find a job in academia. I really do believe that the principal problem is an excess of graduates and a dearth of positions… both inside and outside academia. It’s already difficult to find a middle-level consulting or industry job without a Master’s, jobs that formerly went to people with Bachelor’s… essentially it’s forcing people to seek more education when they otherwise could have acquired similar skills and experience from their paid work. This problem does start with PIs (and universities, plainly) who have an incentive from the perspective of funding and reputation to bring on more PhDs regardless of employment prospects down the road…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that many of the skills that are great for academia are also great for other fields. Many folks in non-academic industries know this. The point is not to completely restructure PhDs, but to 1) normalize non-academic and even non-science pathways for PhDs, and 2) prepare students for the possibility of those careers.