Five weeks ago, I completely severed both tendons in my left pinky. I was just about to start working in the lab, training my PhD student on the initial processing of a peat column from our Falkland Islands trip in December. We had bought a large serrated kitchen knife specifically to slice through 1 ft-square blocks of dense, fibrous peat. As I was trying to get the knife out of the package, the blade went right through the plastic and cut deeply into my finger.

My PhD student was a total champ. She went straight for the first aid kit, while I rinsed my hands under cold water to try to get a sense of how bad the damage was. When I started feeling dizzy and had to sit on the floor, I knew this was more than a bad cut. While my student bandaged my finger, I called a colleague to take me to urgent care.

My colleague and I spent about 15 minutes trying to figure out where I should go, given my insurance policy. We had a vague sense that some places were okay, but not others (it turns out this is not true for emergencies). We even pulled into a walk-in clinic we found on the web that wasn’t even open anymore! I finally did make it to the doctor, and was seen right away. Fortunately, I mentioned to the employee at registration that I had cut myself in the lab, and so she knew to process it as a Worker’s Comp. case (something that hadn’t even occurred to me!).

I was really lucky. I had people I could call who were around when I called them. I had a cool-headed student who administered first aid and was able to stay behind to clean up the mess (wearing gloves!) so the custodian wouldn’t deal with blood. I wasn’t working alone. There are a lot of things that could’ve gone wrong (beyond the fact that I need to be more careful with ginormous knives), and didn’t, partly because of luck, partly because of having competent people around me, and partly because of planning in advance.

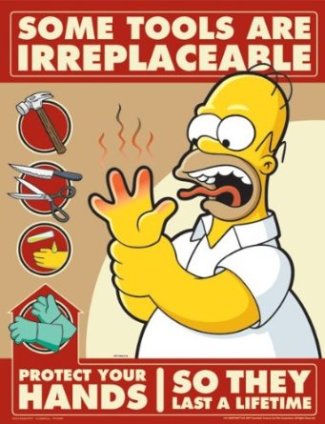

In the aftermath, I’ve been thinking a lot about lab safety. I was the safety manager in my graduate lab, and so I always thought about (mostly chemical) safety in the abstract. We work with a lot of very hazardous chemicals, high-temperature ovens, glassware, high-pressure gases, and other potential dangers, but in my case the injury came from handling an everyday object — a kitchen knife.

How prepared are you and your lab? Most universities require safety training, but these are typically pretty basic and rarely cover the actual hazards you will run into in your own work environment. For that reason, we do a safety orientation and have a checklist on file for every person who works in our lab — even if they just do computer modeling. You never know who is going to be on hand to help you out when something goes wrong. We do an internal review every year in the form of a game of Safety Jeopardy. After my injury, though, I’ve been thinking that approaching safety as an intellectual exercise is not enough.

In training, we make sure students know where the MSDS binder is kept, and where the (well-stocked) first aid kit and fire extinguishers are located. In the field, we try to have as many people trained in first aid and wilderness first response as possible. We provide accessible personal protection equipment and chemical neutralizers for someone responding to a chemical spill (outside the room where the chemicals are kept!). We post the appropriate phone numbers for dealing with chemical, fire, medical, or other emergencies in prominent places (including my cell and numbers for safety officers, senior grad students, and technicians).

But what my injury has really shown me is that when it comes to safety in practice — responding to an incident in the moment — I can do better. I’m thinking that our annual safety review needs to start incorporating some role-playing elements. No matter how many times you’ve read or reviewed a policy, or how confident you are in your ability to think quickly, you’d be surprised at how much that mental preparation goes out the window in the moment.

The real test of any safety policy comes during an incident, which is not when you want to be identifying personal weaknesses or holes in your training. I don’t want my students worrying about where to go after an injury, or who to call to ask for help, or who will take their insurance, or where to find the bandages and gloves and hydrofluoric-acid-neutralizing gel. And I think the only way we can really assess that is with some mock incident drills.

What is your lab’s approach to safety? Do you have an internal training policy specific to your lab? Have you ever done any safety role-playing? Do you have a dedicated safety officer? What do you do now, and what can you do better?

Categories: Professional Development Research Tips & Tricks

A good read for sure. Thanks for sharing so that others can remain safe,

I am reminded of a co-worker’s safety slogan:

” Safety at work, safe tea at home.”

I think every workplace should have:

1. Regular safety engagement sessions

2. A trained safety officer

3. Frequent drills

LikeLike

Off topic completely but I had to share this with someone!

https://engineering.purdue.edu/Stratigraphy/gssp/index.php?parentid=all

LikeLike

When I was very young and mucking about with soldering irons and power saws, one of the best pieces of advice I encountered was: Learn to break the human reflex to catch something you’ve dropped or that has slid off the workbench. (Catching the business end of a hot soldering iron is no fun.)

Another good piece of advice I got much later is: Never point the business end of a gun or sharp object at something you don’t *intend* to destroy! (Problem is: opening modern packaging often really puts that to the test!)

Best wishes for a full and speedy recovery!

LikeLike

Wow! This is making me realize my own lack of preparedness! Your point about what emergency facility you should choose based on your insurance is great- we should all figure this out for ourselves right now!

Another issue for ecologists- if you do field work at all, you should consider taking a Wilderness First Aid Course. I did one through NOLS (http://www.nols.edu/wmi/courses/wildfirstaid.shtml) because the outdoors club at my university sponsored it and allowed others to take it. It was an entire weekend, but I was glad to learn the material and have it in my back pocket while we did remote desert work. For instance, I learned how to take and record vital signs on a piece of paper so I could hand it to the EMS personnel when they arrived, so they get a sense of the recent history of the injury.

Note that NOLS defines “wilderness” as any place where it could take you more than 1 hour to get to definitive care. So even if your field site is an agricultural field outside of town, you might still consider a course like this!

LikeLike