Academics juggle a lot of balls. The absent-minded professor stereotype is, for some of us, an apt one. Because our jobs involve multiple independent demands on our time, we’re often tossed (or hold on to) more balls than we can handle. Balls get dropped, neglected, or stay in the air for far too long after they should have been safely placed on the shelf.

We forget deadlines, studiously ignore emails we should be answering, miss meetings, triage our to-do lists based on what’s most overdue. In my first couple of years as a PI, I’ve seen (and committed) my share of academic courtesy faux pas: never-returned emails, late reviews, late manuscripts, that one person who holds up the special issue, forgetting to notify co-authors of a conference abstract submission*, leaving names off of manuscripts or talks. We may be new PIs still figuring out academic workloads, we may suck at saying no, we may be really disorganized or even inconsiderate or selfish. We’ve all had colleagues who just wouldn’t deliver a draft on time and needed a lot of nagging, or who were so late on a manuscript review we’ve had to give up.

Academic etiquette is one of those stickier bits of professional development that isn’t so much taught as modeled. We know good behavior when we see it — and when it doesn’t inconvenience us — but it’s not something we necessarily discuss in lab meeting or talk about in a professionalism class. Often, it’s something we learn by doing (yay, progressive education!), because we’ve inadvertently stepped on someone’s toes or had them step on ours.

Sometimes lapses are honest mistakes. Sometimes, they become habits. And sometimes, people get reputations.I don’t know how many mistakes or bad choices it takes to get a reputation as a flake or a bad actor, and I hope I don’t find out. I do think that we can get so caught up in the hectic nature of the work that we forget that we’re working with other people — especially around a deadline. I empathize with the fact that life happens (I had a hand surgery earlier this year that really set me back on a lot of projects), and that sometimes when you fall really behind on something, the anxiety it induces makes you neglect it even more.

Ultimately, though, the important thing is to make sure that these are exceptions, rather than the rule. Once missing deadlines becomes a habit, they start to lose meaning. When so many of our interactions are online, they can feel removed from consequences. But there can be consequences, in terms of your reputation. When you’re over a month late on a paper review and not responding to email or phone calls, the editor will remember. If you’re the editor that misplaced a paper for six months, the authors will remember.

Good and bad behavior are obvious. Most of us have been on the giving and receiving ends of both. The repercussions of poor behavior are a bit harder to predict. In a discussion on Twitter, folks were all over the place in terms of whether annoyance at bad behavior would translate to action (maybe that’s because we’ve all made mistakes)? Some folks said they’d drop, or not pursue, collaborations with people who were bad actors. I don’t know if it’s riskier for early career investigators to make mistakes (because we may alienate colleagues in positions of power), or less risky (because we get the New PI Get Out of Jail Free Card). Does grumpiness at someone translate to retaliatory action down the line?

Ultimately, I suspect that being a bad colleague may not be as detrimental as being a good colleague confers benefits. If you develop a reputation for being quick, organized, positive, and helpful, you’ll probably get more collaborations, papers, and invitations than the slow, disorganized, negative, and unhelpful person loses. Either way, I think it’s worthwhile to think about the reputation you’re cultivating, especially if you’re early career (which is when you may be prone to making the most mistakes).

*This post was inspired by my not only forgetting to notify my co-authors of an ESA abstract, but leaving one co-author off entirely. Don’t make important decisions on post-surgery opiates, folks.

Categories: Professional Development

Excellent and thoughtful essay about problems that are plaguing our community. How many times can someone refuse to do a review for a journal before getting a bad reputation? How about 11 from one person, and that from someone who has published in said journal? People who refuse to review are major, major problems for journal editors and NSF program officers. I notice that the same people are not shy about tweeting 10 or 15 times a day. Now, if they just channeled those 15 sentences times 7 days per week into reviews for journals or NSF they might actually have an influence on where science should be headed.

Tweet less, review more. It’s all a matter of where one chooses to spend the twenty four hours it takes for the earth to make one turn on its axis.

LikeLike

Oh, I’m sure there are good reasons– those are probably exceptions, though. My post wasn’t about good reasons; it was about bad behavior. Sometimes advisors do behave badly (and being overcommitted is, in my experience, a common way for that to happen), which puts a student in a really tough position. They have to think about their own careers. I’ve known advisors who say on drafts for a year or more– and I mean sat on, not being throughly checked down to the last detail. That’s the kind of behavior I’m (and I suspect the commenter is) talking about.

LikeLike

I can’t help but respond to the slow to respond advisor one. I’ve seen this happen and it’s really bad for grad students and not something I’m excusing in faculty but students also need to be realistic about the time frames for getting feedback. As a new PI I wanted to be always getting stuff back quickly but this reinforced some bad habits for my students including doing things at the last minute so that either I rewrite things extensively (which doesn’t really help their development as scientists) or it goes in not as strong as it could be. You need to allow enough time for an effective process of feedback which may include several iterations of revisions. I’m imposing time limits on how far ahead they need to give me things in order to get feedback (e.g. fellowship proposals sent to me 1 day before they are due will simply not be read). Additionally, this process may be longer than anticipated if you’re not sending on polished work. It may take several iterations and months of back and forth to get a manuscript ready to submit, particularly if there are substantive issues that need to be dealt with in revision. If a student drops an polished manuscript on my desk and says this will be submitted by X time, we’ll need to have a long conversation about professionalism. Again I want to reiterate that I’m not excusing faulty who do not respond in a prompt manner to students but students (and other collaborators) need to be reasonable about how quickly they can expect feedback and allow enough time for the process to be effective.

LikeLike

Great point. Fast turnaround =! permission to give me something last minute.

LikeLike

Interesting post

The Science Geek

http://www.thesciencegeek.org

LikeLike

I can’t speak for others, but academic etiquette is a big thing for me in how I view other colleagues. Some of the colleagues I think most highly of are those that are prompt, sometimes impressively so, in returning my e-mails and requests. On the other hand, I’ve noticed that it is often very hard to tell the difference between someone forgetting to return an e-mail and someone actually not caring. A few times I had a low opinion of someone because it seems like they refused to even give me the time of day, but it turns out they legitimately forgot or their e-mail was eaten by the spam filter.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on dinosaurpalaeo and commented:

Jacquelyn’s post for your contemplation in case I am late replying/reviewing/authoring 🙂

LikeLike

This post is well timed! I recently had an issue with a collaborator myself, and I think it comes down to both professional and personal relationship balance. People will be forgiving if they’ve established a solid personal relationship, whereas professional lapses are felt more strongly in the absence of a personal relationship.

In my case I’m likely to continue collaborations with the unnamed individual because I recognize it as a lapse, but, I’ve had other, similar, interactions that I’d be less likely to repeat because they’re not grounded in a relationship outside of the collaboration.

So maybe the rule of thumb is, if you’re going to let someone down in academia, make sure it’s a friend. 🙂

LikeLike

One amusing story: When I did my first NSF review, I turned it in early. When I mentioned it to some of my faculty friends (I was a postdoc at the time), they laughed and said the officer will be sure to send me all the proposals from now on.

LikeLike

I think your “reputation” in the hands of others depends completely on the standards of the person doing the evaluation: which is sometimes out of your control. I literally once heard a Dean say to a fellow administrator, “so-and-so is an outstanding professor. He replies to my emails within ten minutes.” According to her, apparently, what makes someone a good faculty member is how quickly they respond to your email?

LikeLike

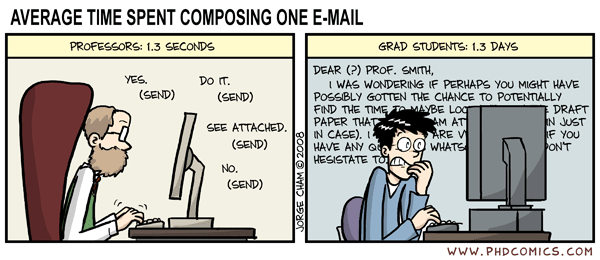

Very cute cartoon!

LikeLike

Any tips on how to deal with an adviser that is guilty of some of this?

LikeLike

That’s a tough one, and depends a bit on the behavior. Advisor management is a really important skill for graduate students to develop. Sometimes it’s a matter of figuring out the best way to get in touch; does a phone call work instead of email? Do you have to physically walk into an office? There may not be a whole lot you can do, but I think at a certain point you can treat the advisor/advisee relationship like any other collaboration: announce that you’re submitting a paper by X, and Y is the deadline for comments. That won’t always work, though. And some things, like letters of recommendation, are out of your hands (lots of reminders are useful here). If you feel like your work isn’t getting credited (through forgetfulness, rather than spite), maybe try to approach the situation carefully. “Hey, here’s a photo of my and my Twitter handle to put on the slides of the stuff I contributed to. I read in a blog that it’s a good way to get your name out there.”

Any other ideas, O Readers?

LikeLike

>>announce that you’re submitting a paper by X, and Y is the deadline for comments

Oh, this is a very bad idea to do with your advisor. If a student did this to me, they would be in a world of trouble. A paper with me as the lead author does not get submitted until I have okayed it, because it’s my personal and my lab’s reputation on the line.

I am usually very prompt, and with senior students a paper is easily submitted within a couple of months from first draft. It takes longer with newbie students. But, for instance, I have been holding on to one draft for 8 months now. Why? Because there is a chance that the paper might be a piece of crap. We did one round of review, but I need to completely rewrite it, and I am not even sure that some of the stuff the student derived in it even holds water. The paper essentially disputes the work of other colleagues, so we have to be 100% sure what we claim is right. So I have been carefully gnawing on it, testing every bit, and reading in detail all the supporting papers to make sure we do not make fools of ourselves (by the way, this is not my only student, I have 8 others and grants to write and classes to teach and conferences to travel to, so it’s not like this one paper is the only thing I have to worry about). Now the student thinks I am just holding his paper for no good reason, I am sure, even though I explained; the reason is I don’t trust what’s in the paper, and I won’t release it until I do.

If he pulled off what you suggest, telling me that he’s submitting with or without my comments by date X, he would a) not be allowed to put my name on it and b) promptly find himself without a research assistantship.

LikeLike

Obviously this is a last resort. If an advisor is drastically holding up publication, that can sabotage the student’s career.

I’m also not talking about a scenario where the student isn’t the lead author. I’m personally not okay with an advisor being the lead author on a student’s paper (eg, a dissertation chapter). That is, to me, of questionable ethics.

If you’re that concerned about the quality of a draft, holding on to it for eight months doesn’t seem like s really effective solution. At that point, I’d be asking the student to replicate results, to present to lab meeting or seminar for feedback, getting friendly review from colleagues, etc. if you have do many students that it takes eight months to go a proper turnaround on a manuscript, perhaps the real pricked is that you have too many students?

LikeLike

The student is first author (lead junior author). I am last author (lead senior author); also, there are only two of us. As for replicating results, it’s not that easy — this is a theoretical physics paper, the results are 20 pages of math and computer simulation. The devil is in the details and the premises employed. I have to check everything in detail, especially because we claim another group is very wrong in their own series of papers, each of which is a lengthy theoretical physics paper.

I don’t want to start a blog kerfuffle, so I am going to ignore you telling me what size my group should be.

I was here to make a point that sometimes there is a good reason, even if the student may not appreciate it, that the paper is being held longer than expected. And that the advisor-advisee relationship is, for better or worse, NOT the same as between other collaborators.

LikeLike